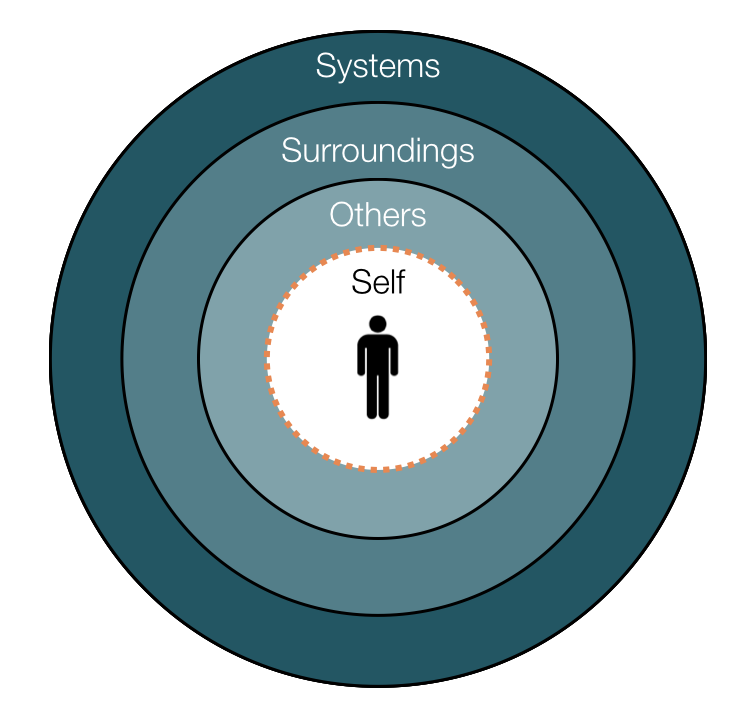

In our May Newsletter we described a Contextual Model designed to help us understand how people make decisions that impact their performance. You will recall that we focused on four general contextual factors (Self, Others, Surroundings and Systems) as primary contributors to determining performance success or failure. The salience or "relative weightiness" of specific factors within these general factors create what we called “local rationality”. Local rationality is a term to describe the fact that individuals perceive and interpret the contextual factors weighing on them in a way that is uniquely their own and makes total sense to them, irrespective of how "irrational" the interpretation appears to an onlooker. This locally perceived and vetted interpretation of the contextual factors weighing on a person, in turn, determines how the person decides, behaves, or performs.

Therefore, to accurately (and thus effectively) hold someone accountable for performance requires that we examine their context before we attempt to “fix” their performance.

Four Skills

We suggest four skills that when applied during an “accountability discussion”, or what we also refer to as a “re-direction” discussion, will help you get an accurate picture of the person’s context.

We have a natural tendency to want to understand and explain what we see as quickly as possible, so we have a tendency to make a guess about the causes of poor performance.

Thus the first skill:

“Don’t Guess”

Whether you are right or wrong in your guess, you are likely to create defensiveness and we have already talked about the negative impact that defensiveness can have on communication (Read the Blog: Dealing with Defensiveness in Relationships).

Additionally, when you guess you can unintentionally influence the person to agree with your assessment even if it is incorrect. So, instead of guessing, become curious and think to yourself...”I wonder why it makes sense to him to do that?”.

This question also weakens the influence of the Fundamental Attribution Error and allows you to entertain factors other than motivation as a cause for failure.

This leads to the second skill:

“Ask Opening Questions”

Start by making sure that your tone of voice is respectful and not accusatory which would most likely be interpreted as a guess and lead to defensiveness.

Don’t ask “Yes” or “No” type questions which would also be seen as guessing, rather simply ask the person to help you understand why they did what they did (a reflection of your curiosity question above).

For example “Can you help me understand why you are doing it this way?”

If you show genuine curiosity and not judgement you will be much more likely to get at the real reason behind the decision and behavior.

Sometimes you will only be able to identify a general contextual factor with your Opening Question, so this brings the third skill into play:

“Ask Drill Down Questions”

Remember, the objective of this discussion is to determine the real reason or reasons behind the poor performance so that you can fix it. If you didn’t get enough information from your first question, then just ask a second, more specific question (i.e., Drill Down Question).

For example Let’s say the person used the wrong tool for the job and when you ask them why they say they didn’t have the right tool. You might drill down by asking something like...”Why didn’t you have the right tool?”.

Just telling them to use the right tool might not fix the problem if the reason they don’t have the right tool is because there is only one available and someone else is using it!” Remember, drill down far enough to find the real reason(s) before you attempt to fix it.

And finally, during the whole conversation apply the fourth skill:

“Listen Completely”

Listening to “what” the person is saying (their words) is only half of the process. To listen completely, you must also pay attention to “how” they are speaking, e.g. their tone of voice, their willingness to maintain eye contact, their body posture, etc. These help you understand the “real” meaning behind what they are saying and will also help you get to the real context that led them to perform as they did.

What's the Point?

Only after you have ascertained the real reason(s) do you have a sufficiently complete and accurate “accounting” of the failure. With this "accounting", you can now help find a fully informed fix that will lead to sustained improvement going forward.